Fairview Cemetery came into use in the early 18th century. The precise date of the first burial has not been determined but an early stone marking the grave of Abram Wright is reputed to bear the date 1702. During the Colonial Period, the appearance was that of a small cleared parcel of land occupied by slate markers with arched tops. Fairview retained this form until the late 19th century when, in imitation of Rural or Garden style cemeteries in many other Massachusetts communities, the local Commissioners of Public Cemeteries caused stone walls and gateways, plot plans and curving avenues to be created. This activity affirmed that Fairview would become the town’s principal place of burial.

Given its status as the town’s oldest, largest and most fashionable resting place, it attracted the leading industrialists, politicians, ministers as well as mill hands and farmers. The variety of personal backgrounds is matched by the variety of grave marker sizes and types. Large granite obelisks are found adjacent to diminutive marble tablets. Arched slate markers from knee height to six feet are present. A variety of other types is scattered throughout the cemetery.

Colonial and Federal Period slate markers, numbering in the hundreds, are well preserved and demonstrate typical artistic conventions and motifs such as death’s heads, portal designs and urns under willow trees. Markers from these periods are divided geographically from later examples by the difference in circulation patterns. Slate markers are placed amid a grassy section that continues to bear evidence of short glacial mounds of earth such as existed prior to centuries of plowing and grading. No avenues exist between stones in this area. These occupy a central rectangular area, known as the Old Division, that abuts Main Street.

Victorian Period gravestones are mostly carved from granite, a locally quarried material. Standard forms such as tablets and chests exist along with unusual examples such as a millstone and a sphere. A single monumental bronze example has been identified. Plots from this period are frequently delineated with curbs and corner posts. Nearly a dozen gravestone carvers, some with several markers to their credit, have been identified.

In addition to occasionally ornate grave markers, some sections of Fairview have winding paths and avenues to provide access to plots. Ground in this area has been graded to reflect gradual changes in elevation. Mounds have been removed to accommodate circulation paths and organization of plots. These changes came in response to trends in cemetery design promoting the picturesque, part of which consisted of renaming the former East Burying Ground to Fairview Cemetery in 1904. The curvilinear portion, known as the East Division was added in 1876. Additional land was again added in 1924 (New Division) and in 1936 (Tadmuck Division). The cemetery continues in use today, but has run out of plots to sell.

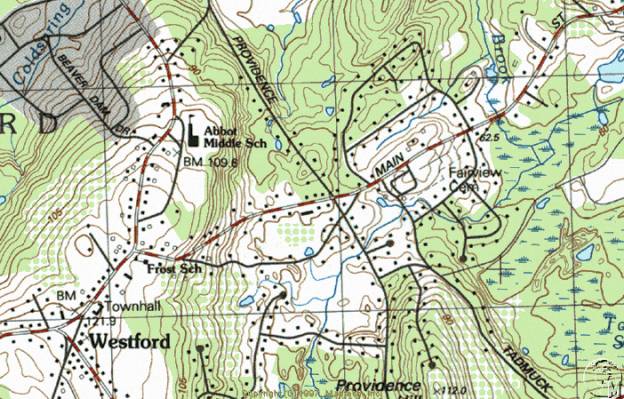

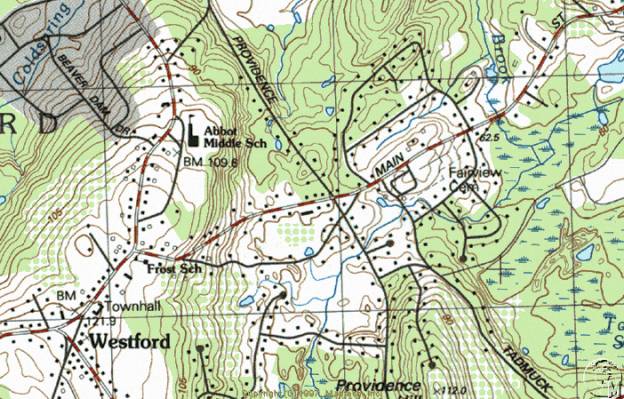

The 18th century appearance of the East Burying Ground was that of a grassy half-acre parcel of short rolling mounds occupied by arched slate gravestones. Located immediately south of Main Street and one mile east of the town center and meetinghouse, the burial ground was mowed and its volunteer growth of bushes trimmed as if it were a farm field. Nineteenth century structures include tombs in the center of the burial ground on two sides of a low earthen mound and two tombs built into the stone wall that lines Main Street. Ornamental trees planted on the grounds include maples, oaks, hemlocks and a variety of evergreen species. Nineteenth century efforts to improve the appearance of the burial ground by grading and constructing avenues among the stones encompassed land on three sides of the Colonial Period burials. A short embankment distinguishes between the rolling mounds of un-tilled earth around earlier burials and the more gradual changes in elevation that were the result of attempts to create a Garden style cemetery.

Stone walls separate the cemetery from Main Street and from Tadmuck Road. The most refined in materials and design is the segment from the corner of the two roads heading east to the main gateway. This is coursed granite ashlar construction three to four feet in height with flat capstone. From the main entrance to the eastern end of the Main Street side is a similar granite ashlar wall of older, uncoursed construction and a similar capstone. The entire wall is approximately 1000’ long. The Tadmuck Road side of Fairview Cemetery is lined with approximately 500’ of two to four foot high cobblestone wall with concrete cap. The rear or south boundary of the cemetery is lined with dry-laid fieldstone that may have been built as part of an adjacent farm field boundary.

The cemetery acquired some refinements in appearance with construction of stone gateways on both the Main Street and Tadmuck Road sides. Most prominent is the main gateway halfway along the Main Street side. Here, two coursed ashlar granite walls curve into the cemetery and toward each other in 90-degree arcs ending in square nine-foot high pillars with square capstones. Secondary pillars mark the departure of the curved sections from the main wall. The corner access at Main Street and Tadmuck Road has a similar arrangement of pillars without the curving wall segments. Both have stones in one pillar bearing the name “Fairview.” The Tadmuck Road entrance is flanked by two round pillars built of cobblestone to a height of seven feet. The eastern end of the Main Street side has an unornamented secondary access through the ashlar granite wall for vehicles that is unornamented. A flight of three narrow steps is built into the Main Street wall near the mid-way point.

Circulation among plots is guided in the eastern and western sections of the cemetery by a system of asphalt paths or avenues, ten feet in width. The more picturesque curvilinear avenues emanate from the secondary Main Street entrance. Diverging to the east and west, paths follow a winding course toward the south and meet near the rear of the parcel, encompassing the 19th century addition to the East Burying Ground. A central winding route nearly bisects these paths around the perimeter. The 1876 plan of this section of the cemetery grounds reflects among these avenues several narrower paths that may have once existed as dirt surfaced footpaths but are now planted in grass and of uncertain direction. The principal gateway on Main Street gives onto two straight parallel avenues heading directly to the rear of the cemetery with a transverse avenue gradually curving to the east and connecting to the more picturesque section of the circulation network. The central 18th century section of the cemetery has no paths between markers. Newer sections of the cemetery in the west and south also have asphalt avenues that are mostly straight except for a loop in the northwest corner, site of current burials. While not consistently apparent, a small number of curbs and low piers mark some edges and corners. The most ornate is close to the secondary entrance from Main Street and has a granite ball and curbstones marking the corner of two converging paths.

Plots in Fairview are delineated in some cases with granite curbstones. These are alternatively flush with the ground or elevated up to a foot above grade. In some cases, such as the Abbot - Cameron plot, the front is lined with stones near grade level while granite slabs at the rear of the plot act as a three-foot high retaining wall, thereby leveling the plot on its sloping site. A single iron fence remains in existence at the Thomas and Edmund Symmes plot. Ornate pales with pointed ends are connected by filigree and low granite posts to enclose an area of approximately eight by ten feet. It is likely that there were at one time many more such plot defining fences but that they have been removed to ease the chore of mowing.

Three tombs exist in Fairview, two of which are incorporated into the Main Street wall. The Town Tomb, marked as such on the 1938 cemetery plan but not so on the actual structure, has a low pedimented slab of granite rising slightly above the level of the wall. Two stout vertical slabs of granite flank the central iron door. Adjacent to the Town Tomb on the east is the Solomon Richardson family tomb, marked with a slate tablet that names nine family members interred from 1817 to 1902 and is set into the granite entry. The only tomb inside the boundaries of the cemetery contains five families: Heywood, Keyes, Proctor, Fletcher and Abbot. The low mound of earth at the south end of the 18th century section has tablets for two families on the east side and three on the north. Dates of these interments range from 1816 to 1926. Construction of doors is primarily granite with some inset slate tablets carved with names and dates. Modern granite tablets with names and dates have been added posthumously during the 20th century to the Abbot marker.

Two buildings exist in the southwest corner near Tadmuck Road. The former Hearse House, also called a tool house on the 1938 plan and now used as the superintendent’s office, is a one-story, side-gabled frame building sheathed in wood clapboards. The plan is two by two bays. Architectural ornament includes gable returns, corner boards and molded trim at the eaves. Modern windows have been installed. The outline of a vehicle door exists on the west elevation, which backs up to the cobblestone wall along Tadmuck Road. The proximity of the door to the wall now prevents vehicles from entering and suggests either that the building was moved or the wall was built after the need for the door was obviated. A shed ell expands the rear of the plan. A modern gabled shed or storage building is oriented perpendicular and immediately adjacent to the former hearse house. Three overhead doors on the east elevation provide access to the interior of the shed.

An open, wood-framed octagonal building with octahedral roof, approximately ten feet across and 12 feet high, is described in town reports at the time of construction as the “Summer House.” Turned posts with jigsawn brackets support the roof. A jigsawn baluster and benches on seven sides rim the floor. A pointed brass finial occupies the peak of the roof.

Fairview Cemetery reflects trends in gravestone development in its variety of slate, sandstone and granite markers. Slate is the oldest surviving material used for marking burials and is carved in arched, shouldered-arched and flat-topped tablets. Ranging in height from one foot to over five feet, this type of marker can demonstrate a relatively crude, hand cut appearance, a well-designed and possibly machine cut sharpness and several levels of workmanship in between.

Quality of workmanship of the slate marker is sometimes obscured by the fact that the stone has deteriorated or been broken. Inscriptions also vary in quality and detail. The simplest have fine, narrow letters with little relief or depth. Some of this type are well organized and clearly laid out. Others are jumbled in the way words are divided among lines. Later slate stones from the 19th century are more likely to demonstrate clear, deep, stylized letters with a pronounced serif and well thought out organization relative to the shape of the stone.

Markers appear in a variety of shapes. Those from the earliest period are most commonly cut in a rectangular form with an arched top, representative of the figurative portal between life and death. The shape is also considered an abstraction of the human head and shoulders. This form of marking the passage from life is a Puritan concept brought from Boston and elsewhere during the region’s period of first settlement. Eighteenth century stones are typically carved with one of a variety of motifs. The earliest marker in Fairview, thought to be that of Abram Wright from 1702, is unidentified. Other early stones have faces inscribed in portals, such as the 1783 slate marker of Ephraim Hildreth. Representative of the spirit of the deceased glancing back into the world of the living while simultaneously offering the living a preview of the afterlife, the portal is rich in Puritan symbolism and attitudes toward the transcendent nature of death. In addition to the portal are rows of diamond trim at the edges of the marker.

The symbol of winged death, in the form of either a skull or abstracted human head flanked by a pair of feathered wings spread wide, occurs frequently on stones carved in the late 18th century. This is another representation of the belief that the human spirit was released at the time of death for the flight heavenward. An example of this design motif is found on the double arched stone of brothers Ezekiel and Timothy Hildreth, who died in 1747 before they turned three years old, possibly because of small pox. They are remembered by a double-arched stone with floral trim and a pair of death’s heads flanked by wings and decorative circles. Circles figure prominently in the design of the slate marker for William Chandler who died in 1757 at the age of 67. Here, the winged skull is sited below the legend “momento mori”, a reminder to the living observers of their impending deaths. At the peak of the arched stone and above all other design features, are three concentric circles that symbolize eternal life and resurrection. Deacon Paul Fletcher, who died in 1735 at the age of 57, is buried beneath a stone with a death’s head, circles and flowers but without wings.

Based on classical influences exerted by the spreading glow of the Enlightenment, new images for gravestone ornamentation rapidly made the older themes seem outdated. Urn and willow designs appear frequently on gravestones from the Federal through the Victorian Period. Both slate and sandstone markers exhibit this late 18th and early 19th century motif that is an icon of sorrow and grief. A sculptural granite example also exists. Change from the puritan death’s head to the classically inspired urn and willow marked a change in the way death was viewed by New England society. Previously, the event was considered a common reality whose dim portent reflected the stern view of life as a struggle for survival. The Post-Puritan view of death adopted a sentimental quality that spoke more of the emotional state of those left behind than of the journey of the deceased, causing the replacement of darkly spiritual carvings with abstract sorrowful imagery. The use of columns in gravestone design, frequently of the Doric order, is evidence of the pervasive influence of imagery popularized by publications and designs featuring drawings of classical architecture. Major Jonathan Minot’s 1806 slate marker has an urn and willow design in its arched top with Doric columns flanking a central panel for the inscription.

A marker type with one example in Fairview is the tablestone used to mark the grave of the Reverend Willard Hall. Here, three vertical granite slabs support a horizontal slate slab inscribed with Reverend Hall’s dates and commemoration of his service to the First Church of Christ in Westford. The grave is also marked by a cast iron Maltese cross placed by the Sons of the American Revolution. The British flag identifies the minister as a Tory.

Additional marker types in the form of obelisks, chests, and tablets with biblical and classical symbolism appeared during the Victorian Period. Obelisks are carved mainly from granite although several early sandstone examples are present. This type of marker was in frequent use from the mid 19th century forward and ranges from six to 15 feet tall. The most prominent example, marking the burial site of the family of John William Pitt Abbot, is carved of pink granite. Its polished facets are inscribed near the base with dates for Mr. Abbot, his wife and three children. This is the largest monument in Fairview. Numerous other obelisks are from the late 1800s and have capstones and smooth, polished granite faces.

Chest markers appear throughout the cemetery with dates from the mid 1800s to the present. These are larger than tablets and are most frequently cut from granite. The William E. Frost (1842-1904) chest marker is an unornamented rectangle with polished front and rear faces. Edges of the marker have a rough quarry-faced finish. The Albert P. Richardson (1843-1903) chest marker, however, has all faces polished smooth and is trimmed with a floral motif and ovolo molding at the top.

Tablets with biblical symbolism appear, usually in marble. A poignant example is that of Agnes Cameron who died eight days after her birth in 1865. She is remembered with a small white marker topped with a lamb, symbol of youth and innocence.

Some non-traditional marker types appear in Fairview. Along the northern boundary of the cemetery is the marker for the mill owner George Heywood (1829-1914) and his family. The inscription appears in the polished circular face of a granite millstone. The rear of the marker has grooves as in an actual grindstone and may have been taken from the Heywood mill located at the crossing of Depot Street over the former Stony Brook Railroad (now CSX). The Griffin family marker is unusually large and has the cemetery’s only spherical ornament. Made of polished pink granite and resting on a stout pier and gray granite base, the sphere measures approximately three feet in diameter. The marker commemorates the lives of Joseph B. Griffin (1816-1896), his wives Deborah (1807-1848) and Eliza (1835-1912) and three other family members.

A single example of a zinc grave marker exists in Fairview and commemorates the Charles J. Searles (1836-1901) family. This unusual marker is the product of the Monumental Bronze Company of Bridgeport, Connecticut, which operated from the 1870s until after WW I. The three-foot high imitation stone is made to resemble quarry-faced granite in the form of a shortened obelisk. The top is ornamented by a rounded finial above a flared molding and hollow shaft. Below the shaft, the base flares in four-peaked fascia, the southerly of which bears the family names. This is the only known zinc monument in Fairview Cemetery but they are commonly found in cemeteries across the nation.

Military markers in Fairview are scattered throughout the cemetery. Charles Brooks is buried beneath a typical low arched marble tablet inscribed with the military unit with which he fought in the Spanish American War. Similar markers appear for veterans of the Civil and World Wars. Soldiers involved in actions prior to the Civil War are remembered by their ranks inscribed with their names, usually on slate markers. Many military markers are redundant, located adjacent to family stones that repeat dates for veterans.

The earliest known gravestone carver’s name to appear is that of I. Hartwell who carved a marble marker for Horace Parker, MD in 1829. Later stones bear carvers’ names and locations such as F. A. Brown of Derry, New Hampshire and A. Stone of Groton. B. Day, Charles Wheeler, T. Warren and D. Nichols, Gumb Bros. all had workshops in Lowell. Such evidence suggests this industrial center to the east was the primary community for buying items not available locally such as gravestones and other manufactured goods. The J. W. P. Abbot obelisk bears the inscription A. MacDonald Field & Co. Aberdeen.

Fairview has evolved into a modified rectangle and is currently known by four Divisions. The Old Division West occupies the center of the plan and abuts Main Street at the north. The East Division is recognizable by its curvilinear path network drawn in the 1870s by Edward Symmes. The New Division comprises a narrow rectangle at the south and was added in 1924. The Tadmuck Division, added in 1936 and landscaped between 1938 and 1953, occupies the west end of the overall plan. While records do not indicate as much, it is possible that, since few remain, footstones were removed as part of past efforts to tidy the grounds. Repairs have been carried out in the cemetery on a regular basis since the 19th century, resulting in visible repairs to some slate stones. Since the material is particularly susceptible to cracking and toppling, several different methods have been used to stabilize markers. There are some which have been re-set in concrete footings poured at ground level. Others have been re-attached at severed points with metal braces and bolts or cemented or glued across fractures. Most stones remain in good to excellent condition, although some slate markers are difficult to read due to erosion. The Cameron family marker appears originally to have had a finial which is now missing. While very little other vandalism has taken place, damage has been sustained in many cases due to scraping by lawn-mowing equipment. However, the large number of remaining 18th and 19th century markers make it possible to get a clear sense of historical burial and gravestone carving techniques in Westford.

Originally called the East Burying Ground (also called Snow’s after the former groundskeeper and neighbor Levi Snow), Westford’s first place of burial came into use before the founding of the town in 1729. While still considered Chelmsford’s West Precinct, Abram Wright was interred here in 1702. This is the earliest recorded burial although there were likely previous occupants. The record for Mr. Wright appears in the 1883 town history written by Edwin Hodgman who claims to have examined all existing markers. This occurred at a time when far more of the inscriptions were legible than is the case today due to erosion and other types of damage. Mr. Hodgman’s usually exacting efforts to reveal town or precinct records for establishment of the burial ground were fruitless. The 1702 stone is unidentified.

Bounds of the burial ground were found in 1753 by a committee chosen for the purpose at town meeting. It appears that even at that time, much of the origins were unclear. After agreeing upon property lines in relation to surrounding farmland, the committee lost little time in erecting a gate and horse mounting block, neither of which are evident today. Adjacent landowners Thomas Cummings and Josiah Brooks donated to the town in 1768 parcels for expanding the grounds by 18 rods to the south and an additional 30 rods in an undetermined direction.

Occupants of the East Burying Ground from the period include the town’s first mill owner, William Chandler (d. 1756, 67 years of age) who operated a fulling mill on Stony Brook near the current Brookside Road, Deacon Paul Fletcher who was chosen as such on January 5, 1733 and who died just two years later at the age of 57, Joseph Underwood (1681-1761) who was responsible for the sale to the town in 1748 of the parcel of land that became the Common, Deacon John Abbot (1713-1791) who was a selectman, school teacher, town clerk and progenitor of a leading family of industrialists, Reverend Willard Hall (d. 1779) who was the Tory minister of the First Parish Church from 1729-1775.

Revolutionary War veterans who fought in the Battle of Concord in April 1775 and were recognized by the Sons of the American Revolution with iron cross markers in 1902 include First Lieutenant Zaccheus Wright (later Captain at the Battle of White Plains, NY), Sergeant William Hildreth, Corporal Hosea Hildreth and Sergeant Major Jonathan Parker who also fought at Bunker Hill.

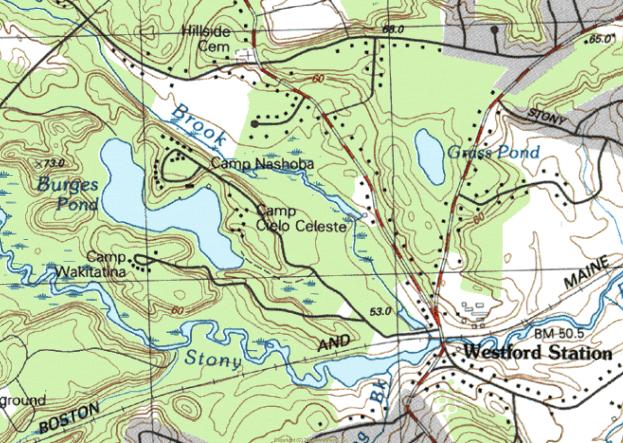

Less well-known residents tell of other aspects of the town’s history. Ezekiel and Timothy Hildreth share a double arched slate marker. Children of Abigail and Joseph Hildreth aged under three years, they both died in January 1747. This and other examples in Fairview of the loss of multiple children remind modern visitors of the hardships of Colonial life. Approximately 300 Colonial Period slate markers occupy the central part of the cemetery. The North and West Burying Grounds (now called Hillside and Westlawn) were in use by this time. These are smaller than Fairview and occupy sites farther from Westford Center.

The transformation from burial ground to the local version of a Rural style cemetery began nearly ten years after the founding in 1831 of Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge. Nationally influential for its landscape designed by horticulturists and landscape architects and its governing body’s intention to beautify the final resting place, Mount Auburn served as a model to cemetery commissions across the country. Over a period of nearly 40 years, Westford’s cemetery commissioners would gradually create a simple version of a Rural cemetery by building walls, grading circulation paths and planting trees and shrubs.

The 1840 town report indicates the stone cutter and Westford resident Nathan S. Hamblin was paid $90 for building a wall and setting stone posts. In the same year, B. F. Keyes was paid for building and painting a fence. No evidence remains of a fence from the period but some portion of the stone wall lining Main Street from the main gateway to the northeastern corner is likely the work of Mr. Hamblin. Levi Snow was paid in 1858 for laying 24 ½ rods of wall (392 feet) which may have been the un-coursed granite section at the east end of the Main Street side. Asia Nutting was paid $101.50 for unspecified stone work in 1868. In 1880 the selectmen reported in favor of building a faced stone wall and began advertising for construction proposals, finally selecting that of George Yapp who lived three miles away on Concord Road near Hildreth Street. By 1883, Mr. Yapp had built the western 580’ feet of wall along Main Street using material quarried in Graniteville, thus completing the 1000’ of granite wall now extant. No mention is made at this time of the granite gateways but they were likely built at this time.

A new hearse house was built in 1870 by George Drew. This is likely the existing Superintendent’s Office at the southwest corner of the cemetery. Given the expansion of the grounds, the former hearse house has probably been moved so as to remain in a remote corner as the cemetery expanded. Town reports note that Mr. Hamblin was paid in 1871 for constructing the Town Tomb built into the Main Street wall. The first mention of the tomb appears in cemetery records on February 12, 1871. Prior to its construction, people who died during months when digging was impossible were temporarily interred in private tombs of other townspeople.

Cemetery commissioners acquired appropriations for another method of improving the appearance which involved re-setting older gravestones, presumably to put upright those that were leaning or had fallen. Colonial Period stones are now arranged in neat rows, oriented north to south, with most family members close together. The current absence of footstones may have come about as a result of this effort to tidy the grounds. Commissioners not only improved the burial ground’s appearance in these years but bought 38 rods of land from Joseph Henry Read in 1874 in order to expand the space available for burials.

The purchase of additional space and the community will to improve the burial ground led to a survey of the land in 1876. Locally prominent civil engineer Edward Symmes, a Fairview occupant who lived from 1806-1888, was retained to create a plan in a style fitting a Garden cemetery. Mr. Symmes also created the 1855 map of Westford. The result of the 1876 survey is the existing network of curvilinear paths and individual plots in the East Division. Water features were an integral part of Garden style cemetery planning for their ability to encourage reflection and to impart a sense of calm. Mr. Symmes appears to have intended a fountain to be built in a circular plot near the center of the cemetery, which, by the time of the 1938 cemetery plan, had been precluded by the plot’s use for a burial.

An important aspect of the process of transforming the East Burying Ground into the local version of a Garden style cemetery was that of deciding upon a new name. There were “many ladies” who, at the invitation of the cemetery commissioners, signed a petition in 1896 suggesting the name Fairview. The petition was immediately granted.

In addition to the creation of picturesque paths and avenues, cemetery commissioners created in 1894 a procedure for residents to reserve lots and either to pay the town one or two dollars annually for maintaining them or to establish a perpetual care fund in the amount of $50 to $100, the interest of which would pay for labor to trim shrubs and mow grass. Interest in establishing such funds was intense for the subsequent five years as can be seen in the legend “Perpetual Care” carved on many markers from the period.

A campaign of tree planting was begun in 1895 which continued for many years. Maples, red cedar, spruce and hardy shrubs were set out. Ornamental plantings continue to be an integral part of the designed landscape although few examples have survived from the late 19th century. The final addition to the cemetery during the period of refinement was the octagonal Summer House. The open-walled building was designed and built in 1896 by local carpenter William Edwards who was responsible for many other Westford buildings such as the 1870 Town Hall and the 1895 J. V. Fletcher Library.

Westford Residents interred at Fairview during the 19th century include the full range of economic, educational and social backgrounds. Indeed, nearly all burials taking place in the town by the end of the period occurred in Fairview due largely to its improved landscape. John William Pitt Abbot, Esq. (1806-1872) is buried with his family on a plot distinguished by the tallest marker in the cemetery. Mr. Abbot’s prominence in the community stemmed from his practice of law, title of president of the Stony Brook Railroad, involvement in the family industry of woolen manufacture in Graniteville and Forge Village, service to the town as selectman, town clerk and Westford Academy Trustee, service to the church as clerk for 40 years, and to the commonwealth as representative and senator. George R. Moore (1817-1892) is another mill owner buried in Fairview. He owned a number of companies in Chelmsford and the woolen yarn mill in the village of Brookside in Westford. Another resident of Fairview is Luther Wilkins, a farmer who lived with his wife and four children on the edge of the village of Westford Center. Mr. Wilkins’ son Luther E. Wilkins served in the Union Army in the Civil War. Other residents from the period include the town physician Dr. Benjamin Osgood who died in 1863 and Ira Leland (b. 1798), a butcher and farmer from Westford Center.

The cemetery had only a few groundskeepers during this period. From 1835 until his death in 1869 it was the farmer Levi Snow, who lived across the street and for whom the burial ground was occasionally called prior to its being renamed Fairview. His son George Snow performed the duty for two years until Samuel M. Hutchins took responsibility in 1871 and kept it until 1893. Mr. Hutchins occupied the house across Main Street from the cemetery after Levi Snow. Albert P. Richardson was the town’s Cemetery Superintendent and maintained Fairview into the 20th century until the time of his death in 1902.

Two parcels of adjacent land were added during the early 20th century to the cemetery’s southern boundary. The first was in 1924 and is now called the New Division. In this narrow rectangle, circulation paths adhere more closely to a grid pattern. Another parcel was added in 1936 to the western boundary abutting Tadmuck Road. A plan of the parcel from that year shows it outlined with dry-laid fieldstone walls such as a farmer might build to clear the land. Town reports from the years of the Great Depression contain sections that describe work done by members of the Works Progress Administration (W.P.A.). The W.P.A. report for 1938 discusses stone wall construction that was planned to enclose two sides of the cemetery, suggesting the existing cobblestone wall was W.P.A. work performed at that time.

Family members and friends of those interred established numerous trust funds to pay for maintaining plots. Markers are carved with the legend “Perpetual Care” as a way to notify groundskeepers of which plots get constant attention. The words may also have been a notice to passersby that the occupant enjoyed a certain level of status among cemetery residents. Costs for reserving burial plots during this period was two to five dollars. Perpetual care required the establishment of a trust fund, usually around $100. It appears from names printed on gravestones that, while a handful of people with apparently Irish surnames were buried in the 19th century, there were very few non-English occupants of Fairview until after the addition of the New Division in 1924.

Markers were placed in 1902 at the graves of Revolutionary War veterans by the patriotic and historical organization Sons of the American Revolution. Westford veterans who had been at the Battle of Concord received the S.A.R. emblem, an iron Maltese cross with an image of Daniel Chester French’s sculpture entitled The Minute Man. A Soldiers’ Lot, established in 1906, was reserved for veterans of the Civil War. In 1909, the town received from the United States Government six stones for marking graves of Civil War veterans. These are marble with low arched tops.

A small section exists on the 1938 plan of the cemetery labeled “Strangers’ Row”. The 1876 version of the plot plan of Fairview makes no mention of this parcel and was probably reserved for the indigent or for those simply with no family nearby. The plot is approximately 15’ by 30’ and has no markers however a total of 14 people were buried in the plot from 1907-1939. Sadly three of these are listed in cemetery records as “Unknown”.

Residents of Westford from the period who had an impact on town history and who occupy Fairview Cemetery include an array of industrialists, town officials, farmers and politicians. As in all other periods, members of the Abbot family of woolen mill owners were interred here. Several generations of this family were responsible for building the mills and much of the neighborhood of Graniteville and Forge Village with their side streets of worker housing. Adjacent to the J. W. P. Abbot family marker is that of Allan Cameron (1822-1900), a Scottish immigrant who worked first as a machinist and later operated a woolen yarn manufacturing concern. Mr. Cameron is the namesake of a former public grade school in Forge Village and was a family friend and business associate of the Abbots. George Heywood (1829-1914) was also an industrialist but on a smaller scale. He operated a grist mill at the Depot Street crossing of Stony Brook in the second half of the 19th century. Mr. Cameron and Mr. Heywood were commissioners of public burial grounds from 1892 to 1897. Frank Furbush (1861-1940) owned a gas station and auto repair shop in the village of Graniteville in 1921. In addition to his work on cars, Mr. Furbush acted as a manager at the woolen machinery manufacturing firm C. G. Sargent and Sons in Graniteville.

William E. Frost (1842-1904) was a very active public servant and is interred in Fairview. Mr. Frost worked as preceptor of Westford Academy from 1872 to 1904, and was namesake of the William E. Frost School on Main Street. He was educated at Bowdoin College and is said to have brought modern educational practices to Westford Academy. He was involved in the management of the J. V. Fletcher Library, and was a commissioner of public burial grounds from 1892 to 1897. Albert P. Richardson (d. 1902) was cemetery commissioner and caretaker of Fairview Cemetery. Farmers occupy many plots in Fairview. Oren Coolidge (1800-1872) who lived at 17 Forge Village Road for many years is interred here. Wayland Balch (1839-1937), the latest living Civil War Veteran from Westford, occupied farm houses at 24 Boston Road and 246 Concord Road during the late 19th century. He found his final resting place in Fairview.

Politicians of some note are interred here. Herbert Ellery Fletcher (1862-1956) occupies, with his wife Christina (1846-1912) and her family a granite above-ground tomb probably built with material taken from Mr. Fletcher’s quarry. In addition to operating the town’s largest granite quarry and a successful construction concern, Mr. Fletcher served in the state senate from 1901-1903, performed duties as delegate to the 1916 Republican National convention, and served in the Massachusetts General Court. He was a graduate of Westford Academy. Joseph Henry Read, (d. 1901) also a politician, served in local and state government and was a native of the town. He graduated from Westford Academy in 1855 and went on to become selectman, school committee member, county commissioner and a representative to the Massachusetts State Legislature.

Nettie Stevens (1861-1912) is distinguished among those at Fairview by virtue of her outstanding accomplishments in the field of biology. After studying at Westfield Normal School and completing the course of study in half the usual time, Ms. Stevens took a job teaching at Westford Academy from 1885 - 1892. She then attended Stanford University, graduating with a M.A. in 1900, and Bryn Mawr, teaching and earning a Ph.D. in 1903. The daughter of a local carpenter and graduate of Westford Academy, she died prematurely at Johns Hopkins University Hospital due to a fall in 1912.

Lieut. William Metcalf (1819-1900), who is interred in Fairview, was a Civil War Veteran and native of England. Mr. Metcalf worked as a mechanic, served in the 16th Massachusetts Infantry and lived near the corner of Boston and Littleton Roads. He was remembered after his death in 1900 by his son who commissioned the Metcalf Civil War Memorial, a bronze statue in Westford Center dedicated in 1910 to all Civil War veterans from the town.

Non-Anglo names appear in increasing numbers during this period. While many Irish, English, Russian and Polish immigrants worked in factories in the town starting in the 1850s, Fairview seems to have been favored by members of long-established Westford families. Those with surnames not of English extraction, such as O’Brien and Walkovich begin to appear in the parcel of land added to the cemetery in 1924.

The history and development of the East Burying Ground, renamed Fairview Cemetery in 1896, follow a path similar to many other cemeteries in New England. As in other communities, Fairview began during the 18th century as a cleared but otherwise unimproved parcel dedicated to burial of town residents. Major changes occurred as a result of 19th century trends in landscape design. These trends combined with the spirit of community involvement as seen in the numerous fraternal and social organizations of the time as well as the desire among rural residents to imitate more stylish urban examples of houses, dress, cemeteries and other aspects of life, combined to guide the will of Westford residents to create Fairview Cemetery.

Fairview Cemetery comprises all of the land within the boundaries of the cemetery. It is bounded by Main Street on the north and by properties on Fairview Drive on the south and east. Tadmuck Road forms the western boundary. The cemetery encompasses 10.45 acres, described by the assessor’s office as parcel 170 on map 27.

Boundaries of the cemetery were determined by the Westford Historical Commission and by the consultant. Boundaries include all gravestones, burial-related buildings, structures, circulation paths and ornamental plantings. Stone walls encircle the cemetery and mark all boundaries.

SKETCH MAP NORTH

TOWARD TOP

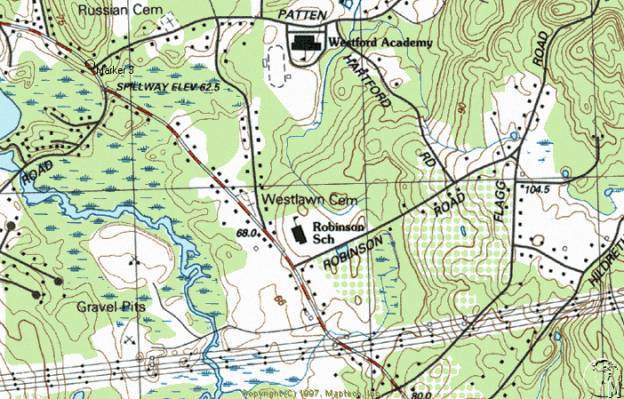

While the name Westlawn Cemetery implies existence of characteristics of the Rural Cemetery movement inspired by construction of Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, the landscape layout, appearance and gravestone art of the burial ground adhere more closely to design characteristics from the Colonial Period. Acquired from local farmers by the town as a burial ground in 1761, it was originally called the West Burying Ground. Many of those interred here are significant in the history of the Town of Westford. War veterans, mill owners and operatives, farmers and business people occupy the approximately 400 visible burials. Members of the Robinson, Prescott, Day, Fletcher and other families influenced the town’s history and appearance and continue to do so by virtue of their artfully carved gravestones.

Markers are made primarily from slate although many granite, sandstone and marble examples are present. Colonial and Federal Period grave markers appear in the form of arched, shouldered-arched and flat-topped tablets, the largest of which belongs to Colonel John Robinson, leader of Westford minutemen at the Battle of Concord on April 19, 1775. While Colonel Robinson’s slate marker has a refined urn and willow motif in its arched top, other slate markers have more primitive designs of death’s heads, faces inside portals and winged skulls.

Monuments from the Victorian Period take the form of obelisks and chests as well as tablets. Slate continued to be used after the Federal Period although marble and granite became more common. The Carver family chest marker was carved in the late 19th century from brown granite and placed atop an earthen mound near the western corner of the cemetery. This is one of Westlawn’s larger and more ornate markers and represents a departure from the simpler tablet form. It was probably during this time that residents placed granite curbs and low corner stones around the perimeters of some plots.

Grave markers are arranged in rows oriented east to west with inscriptions on older stones typically facing south. Three tombs are built in a row parallel to Concord Road, one of which has a retaining wall built of brick bearing inset slate tablets inscribed with names and dates of those interred. Other tombs are earthen mounds four feet in height with granite entry surrounds and iron doors.

Land comprising the West Burying Ground belonged in the Colonial Period to Samuel Parker, a local farmer. The appearance at the time was likely that of a field of grass with a few small slate gravestones. The triangular, flat, grass-covered parcel is located in the pointed vertex of the junction of Concord and Country Roads.

Entrance to the cemetery is thorough openings in the fence along the Concord Road (south) side and at the eastern point of the triangle where Concord and Country Roads meet. The long southerly edge is broken at about the mid-point by a pair of low granite posts with mounts for iron hinges. Gates which hung from the posts are no longer extant. Additional entry is through a gap in the fence at the eastern end. Boundaries of the cemetery are lined on the south and half of the west edge with chain-link fence four feet in height. The northern boundary and half the west have a two-foot high fieldstone wall. A modern flagpole occupies a site just inside the east entry. Rows of pine trees form a line just inside the south and north walls.

Plot definition occurs in 17 instances with simple granite curbs located flush with the ground or as much as 18 inches in height. The Blood family plot has curbing laid at ground level. Many have corner piers that rise slightly above the level of the curbstones. The multigenerational Day family plot, with its varied slate, sandstone and granite markers, is enclosed with this type of border. The Wright family plot near the west end has four-foot high granite obelisks, unique in the cemetery, to mark its edges. Nearby, the Hildreth-Davis family burials have a granite step to access the slightly elevated plot. Curbs enclose square and rectangular parcels of from eight to twenty feet per side and are more common at the west end.

Westlawn Cemetery reflects trends in gravestone development in its variety of slate, sandstone and granite markers. Slate is the oldest surviving material used for marking burials and is carved in arched, shouldered-arched and flat-topped tablets. Ranging in height from one foot to over five feet, this type of marker can demonstrate a relatively crude, hand cut appearance, a well-designed and possibly machine cut sharpness and several levels of workmanship in between. Quality of workmanship of the slate marker is sometimes obscured by the fact that the stone has deteriorated or been broken. Inscriptions also vary in quality and detail. The simplest have fine, narrow letters with little relief or depth. Some of this type are well organized and clearly laid out. Others are jumbled in the way words are divided among lines. Later slate stones from the 19th century are more likely to demonstrate clear, deep, stylized letters with a pronounced serif and well thought out organization relative to the shape of the stone.

Markers appear in a variety of shapes. Those from the earliest period are most commonly cut in a rectangular form with an arched top, representative of the figurative portal between life and death. The shape is also considered an abstraction of the human head and shoulders. This form of marking the passage from life is a Puritan concept brought from Boston and elsewhere during the region’s period of first settlement. Eighteenth century stones are typically carved with one of a variety of motifs. The earliest marker in Westlawn, that of Bridget Read who died in 1760 at the age of 30, exhibits a death’s head in a carved arched portal. Representative of the spirit of the deceased glancing back into the world of the living while simultaneously offering the living a preview of the afterlife, the portal is rich in Puritan symbolism and attitudes toward the transcendent nature of death. In addition to the portal and death’s head are abstracted floral patterns at the edges of the marker and the legend “momento mori”, an encouragement to the living to remember that death is imminent. Mrs. Rebecah Prescott, wife of Lieutenant Jonas Prescott, who died in 1795 at the age of 65 is remembered by a stone with floral trim and a death’s head inscribed inside an oval.

The symbol of winged death, in the form of either a skull or abstracted human head flanked by a pair of feathered wings spread wide, occurs frequently on stones carved in the 18th century. This is another representation of the belief that the human spirit was released at the time of death for the flight heavenward. An example of this design motif is found on the stone of Elizabeth Marshall who died at the age of 36 in 1789. Her marker has the legend “momento mori” inscribed in a banner below the symbol of death.

Based on classical influences exerted by the spreading glow of the Enlightenment, new images for gravestone ornamentation rapidly made the older themes seem outdated. Urn and willow designs appear frequently on gravestones from the Federal through the Victorian Period. Both slate and marble markers exhibit this late 18th and early 19th century motif that is an icon of sorrow and grief. Change from the Puritan death’s head to the classically inspired urn and willow marked a change in the way death was viewed by New England society. Previously, the event was considered a common reality whose dim portent reflected the stern view of life as a struggle for survival. The Post-Puritan view of death adopted a sentimental quality that spoke more of the emotional state of those left behind than of the journey of the deceased, causing the replacement of darkly spiritual carvings with abstract sorrowful imagery. The use of columns in gravestone design, frequently of the Doric order, is evidence of the pervasive influence of classical imagery popularized by the Enlightenment. Lieutenant Jonas Prescott’s 1813 slate marker has an urn and willow design with Doric columns and floral patterns at the borders. The Jonas Hildreth slate marker from 1808 is edged with Doric columns topped with pineapples flanking a central panel with names and dates. The arched top bears the image of an abundant willow tree weeping over a classical urn.

Additional marker types in the form of obelisks, chests, intricately carved Gothic designs and tablets with biblical and classical symbolism appeared during the Victorian Period. Obelisks are carved mainly from gray granite with one example resting on a pink granite base. This type of marker is typically around six feet tall and was in frequent use from the mid 19th century forward. The earliest example, marking the 1829 burial site of John Blodgett, was carved of rough cut granite without ornament. Others are from the late 1800s and have capstones and smooth, polished granite faces. Lawrence, Leighton and Herrick family markers are of this type.

Chest markers in Westlawn are granite, some with a finely polished finish. The Carver Family monument from the 1890s is the largest and most ornate example with its half-round crested top, colonettes with carved floral ornament at the corners and bold lettering at the base. The Day family plot has a granite chest marker for Isaac (1826-1898) and Lucy Day (1832-1927) with a scroll top, comparatively rough finish and little other ornament.

Gothic design motifs in the form of vegetation and architectural detail are applied to marble markers from the mid 19th century. Carrie Rathbone, (d. 1857, 26 years of age) is buried beneath a marble tablet with scrolled sides and top, ballflowers and acanthus leaves emanating from the volutes. The inscription is placed in a central raised panel. Isaac Day Jr., (d. 1856, 58 years of age) resides beneath a marble cruciform marker with brackets, floral trim, shouldered sides suggestive of an architectural gable and a finial in the form of a cross.

Victorian Period designs in addition to the Gothic include biblical and classical references. Stephen (d. 1842, 35 years of age) and Catherine Hutchins (d. 1880, 70 years of age) have matching stones carved with hands pointing heavenward. The pointed tablets are otherwise unadorned. A marble marker on the Hildreth-Davis plot has a segmental arched top and a bundle of wheat set in a recessed oval. Sheaves of wheat are symbolic of the full life lived by the person interred, a secular sentiment of the period. The Jeremiah Cogswell stone (d. 1820, 82 years of age) is marble carved with an urn draped with swag in the arched top. Abel Fletcher’s (d. 1861, 72 years of age) marble marker has the image of two hands clasped in a handshake, framed in a recessed oval. This may be a reference to the person’s trustworthy nature.

Three earthen tombs line the southern boundary of Westlawn Cemetery. The westernmost is the Levi Prescott Family Tomb. It is comprised primarily of an earthen mound five feet in height with an entry made of granite slabs and flanking walls of mortared granite fieldstone. Paired iron doors with circular ring pulls provide access to the interior. The inscription “Levi Prescott’s Family Tomb 1839” marks the top granite slab. Nearby to the east is the Patten-Prescott Tomb consisting of a brick retaining wall with granite capstones and three slate tablets recessed in the wall. The westernmost tablet bears the names of James and Isaac Patten and the date 1812. Deacon Oliver Prescott who died in 1803 and Joseph Prescott who died in 1813 occupy the central part of the tomb. The eastern tablet commemorates Eben Prescott who died in 1811, Hannah and Franklin Prescott who both died in 1812. Family member Cora B. Conant was interred here in 1977. The Leighton family tomb is the easternmost. The earthen mound here is lower than the other tombs, around three feet. The granite retaining wall is approximately two feet high and six feet long with a sandstone tablet in the center. Inscriptions commemorate the lives of Sarah M. Leighton (1778-1873) and her two children Sarah A. (1818-1842) and Reuben (1821-1824).

Westlawn’s most unusual marker has the shape of a stepping stone for mounting horses and carriages and may have actually served the purpose at the tavern in nearby Forge Village. Three steps rise along the northwestern edge of the Luther P. Prescott family marker which has a flat top three feet above grade. Seven Prescott family members, interred between 1885 and 1935, are commemorated by the rough-cut gray granite stone.

At least two 20th century military stones exist in Westlawn. A small rectangular marble marker with segmental arched top marks the resting place of Steven Kostechko (1914-1955) who served the country in World War II. Carl F. Haussler (1892-1964) served during both World Wars and is remembered with a marble marker carved with a cross inscribed in a circle. The stone is flush with the ground.

Cast iron and stone markers placed posthumously commemorate military service of many residents of Westlawn. The Sons of the American Revolution were responsible in 1902 for placing nearly a dozen iron crosses on stakes at the graves of veterans of the American Revolution. The Maltese crosses are approximately eight inches across with a circular emblem in the center bearing the image of Daniel Chester French’s statue in Concord entitled The Minute Man. Crosses placed by the Grand Army of the Republic commemorating service in the Civil War are five-pointed iron markers. The Colonel John Robinson Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution placed in 1968 a stone marker with bronze plaque near the Concord Road gateposts recognizing the military leadership of Colonel Robinson and his interment in Westlawn.

Repairs have been carried out in the cemetery on a regular basis since the 19th century, altering only slightly the appearance from its Colonial Period beginnings. Slate stones are particularly susceptible to cracking and toppling given the weak structural nature of the material. Several different methods have been used to stabilize markers. There are some which have been re-set in concrete footings poured at ground level. Others have been re-attached at severed points with metal braces and bolts or cemented or glued across fractures. Most stones remain in good to excellent condition. Some slate markers are difficult to read due to erosion. While very little vandalism appears to have taken place, damage has been sustained in many cases due to scraping by lawn-mowing equipment.

Aside from routine maintenance, repairs and some deterioration over time, few changes have occurred in Westlawn. While records do not indicate as much, it is possible that, since few remain, footstones were removed as part of past efforts to tidy the grounds. However, the large number of remaining 18th and 19th century markers make it possible to get a clear sense of historical burial and gravestone carving techniques in Westford.

Westford’s West Burying Ground first came into use as a public burial ground in 1761 when the parcel was given for the purpose to the town. At least one burial, that of Bridget Reed in 1760, had taken place here prior to acquisition by the town. Approximately two dozen stones survive from mid 18th century. Burials at that time were conducted with a minimum of ceremony. Gravestone ornament was restrained and the surrounding landscape was allowed to appear as a grassy plot marked by slate headstones. Treatment of burial places remained austere until the mid-19th century when townspeople began efforts to improve the burial ground landscapes. This appears to have been motivated by the popularity of more exuberant funerary ornament as at Mount Auburn Cemetery founded in Cambridge in 1831, and by antiquarians’ interest in recording and stewardship of historic artifacts.

While many cemeteries, including Fairview in Westford, show signs of imitation of Mount Auburn Cemetery in their complex plot plans, curving circulation paths and ornate entrance gates, West Burying Ground acquired only a picturesque new name, “Westlawn”. It was not the subject of any structural improvements or pathways among burial plots. Slate markers from the 18th century remain largely unchanged, although they are surrounded by Victorian Period markers of granite and marble.

The most basic maintenance schedule has allowed the cemetery to retain much of its historic appearance by virtue of the densely grouped slate markers near the core, the small scale of markers and the simple landscape unencumbered by modern paths and furniture. Burials continued in Westlawn until 1999.

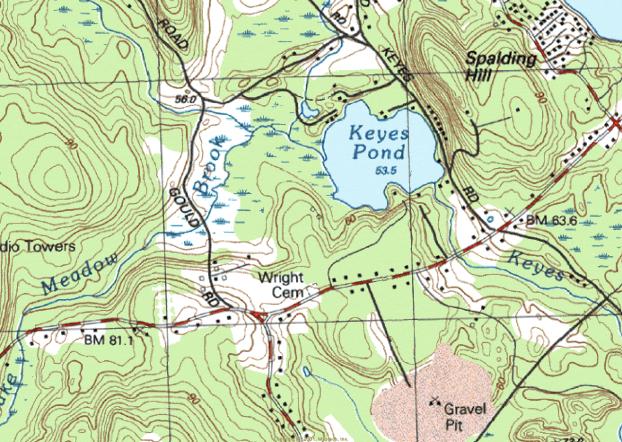

West Burying Ground occupies land that had been in use since the early 18th century as farmland belonging to Deacon Joshua Fletcher (d. 1736), original member of Westford’s First Parish Church in 1729 and one of the town’s 89 original taxpayers. Mr. Fletcher also served as town clerk and selectman at the first town meeting. He resided ¼ mile east of the burial ground. Samuel Parker (b. 1717) married Sarah Fletcher (b. 1719), daughter of the deacon, and inherited his father in law’s land. In 1761, Mr. Parker sold the parcel comprising West Burying Ground to Nathan Proctor who, according to town meeting records from May 15, 1761, donated the parcel to the town. Those at the meeting voted to accept one half acre of land for a “burying place”, thereby creating the West Burying Ground, the town’s second. The first, originally called the East Burying Ground, is now called Fairview and came into use around the turn of the 18th century. It is one mile east of Westford Center (Main Street near Tadmuck Road).

There was at least one person, Bridget Read, who was interred on the parcel prior to its acquisition by the town. Other burials whose markers do not survive may also have occurred before the official establishment of West Cemetery. Gravestones from the 1700s are typically located very close together. Family members tend to be adjacent to one another, frequently aligned in the order in which they died. No segregation based on ethnicity, occupation, military service or wealth is apparent. Most stones are around the same size, two to four feet high by one to three feet wide. Maintenance of the burial ground during this period was the responsibility of a nearby resident. Duties consisted of mowing grass which was remunerated by the town on a yearly basis and digging graves for which the caretaker was paid piecemeal. Approximately 150 markers from the period exist in the cemetery.

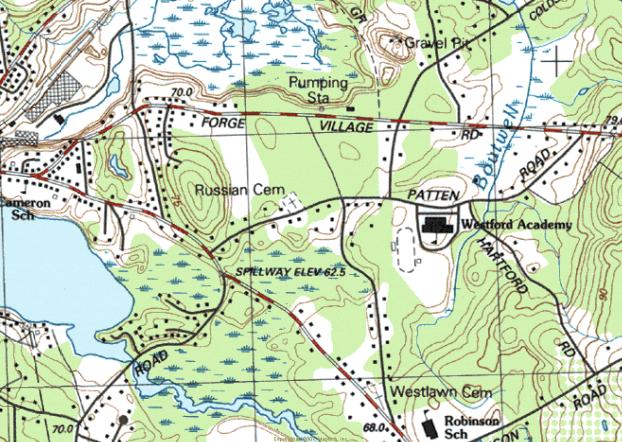

Eighteenth century residents of Westford who are buried in West Burying Ground include industrialists, Revolutionary War veterans, local politicians and farmers. Around 1680, the blacksmith and Groton landholder named Jonas Prescott (b. 1648) built the first iron works in nearby Forge Village and began its 300-year history of industrial activity. Mr. Prescott lived with his wife Mary at the southwest corner of Pine and Town Farm Roads. He mined bog-ore in Groton to be smelted into iron at the mill site on Stony Brook. The iron was used for making candlesticks, farm tools and household items such as irons according to local historian Gordon Seavey’s 1988 local news article on the influence of Stony Brook. Mr. Prescott might also have operated a grist mill at the outflow of Forge Pond at this time according to town histories of Westford and Chelmsford. He and his descendants who influenced the development of the town are interred at the West Burying Ground. These included the town clerk Jonas Prescott Jr. (ca. 1678-1750) and his wife Thankful Wheeler, Jonas Prescott III (b.1703) and his wife Esther Spalding (b. 1705) and Lieutenant Jonas Prescott (1727-1813) who served in the French and Indian War, the Massachusetts General Court from 1758-69 and is described as a “forgeman” in the genealogy in the Hodgman town history. The Prescotts made an immeasurable impact on the town by beginning its industrial activity and maintaining a family interest for several generations.

Westford’s highest ranking Revolutionary War soldier, Colonel John Robinson (1735-1805), is buried under West Burying Ground’s largest slate marker. Colonel Robinson led three companies of minutemen (approximately 160 men) from Westford Common to Concord’s North Bridge on April 19, 1775. While some vagueness surrounds the particulars of the Westford men’s involvement here, it seems clear that they took part in harassing the British troops on their retreat to Charlestown. Colonel Robinson was described as a tall man of great energy who, while fighting at Bunker Hill in July, 1775, was “exposed to instant death, yet doing his duty; now leaping upon the parapet, a target for the advancing foe, and now reconnoitering with the ill-fated McClary, the position of the enemy to find the best way of repelling his persistent attacks; showing himself everywhere the efficient and strong-hearted man.” This was according to a 19th century recounting. Colonel Robinson also served as selectman from 1771-1773. He lived less than a mile from Westlawn on the road that now bears his name. Prior to its being renamed Westlawn, there was consideration in 1902 of giving the former West Burying Ground the name Colonel John Robinson Cemetery. During this period, an iron fence, donated by hearse driver and cemetery superintendent Albert Richardson in 1892, surrounded the Robinson family plot. This was a common form of delineation within burial grounds at the time and was probably not the only example. There are no longer any plot-defining fences in Westlawn.

Approximately 15 additional veterans of the Revolutionary War are interred in the West Burying Ground. This is also the final resting place of Lieutenant Timothy Fletcher (d. 1780) and Ensign Jacob Robinson (d. 1778 at age 68) veterans of the French and Indian Wars as well as Joseph Reed, Calvin Howard and Aaron Parker who all served in the War of 1812.

Two groups of grave markers have poignant ability to reveal potential hardships of 18th century existence. Adjacent to Colonel Robinson’s gravestone and that of his wife Huldah, is a slate double marker for two young girls. These are Betty and Mehitabel Robinson, aged five and eight years. They share a stone due to the proximate dates of their deaths which came 11 days apart in the late summer of 1775. This was just weeks after Colonel Robinson’s involvement in the Colonial defeat at the Battle of Bunker Hill in July. A similar tragedy befell the family of Silas and Hannah Read in 1777 when their children Silas, aged two years, Hannah, aged seven months and Betty, aged four years died between the 18th and 24th of September.

Networks of trade relations can be partially determined by examining the names and locations of gravestone carvers who sign their work. At least one marker exists in Westlawn that may have been carved by a member of the well-known Park family of Groton stone carvers. This is an 1820 marble marker signed by John Park. Since Mr. Park died in 1811, the stone may be post dated. At least one gravestone worked by the carver named L. Parker exists in Westlawn. Mr. Parker showed an understanding of classical design motifs in the form of Doric columns flanking the central inscription with pineapples and urn and willow above, all present on Jonas Hildreth’s 1805 slate marker.

Changes in the appearance of the cemetery began to occur after 1830 when slate was less frequently used for gravestones. Marble and granite gradually replaced slate, probably for their improved resistance to delamination and exfoliation. In addition to their superior durability, these materials present a very distinctive appearance in comparison to slate. Previously unavailable colors, shapes, inscription types and increased scale were all possible with the new materials. Also, the art of the gravestone carver was advancing in the face of modern imagery drawn from Victorian period biblical and iconographic sources.

With the annual publication of town reports beginning in 1840, it is possible to understand how the town’s burial grounds were operated and maintained. The types of tasks, volume of expenditures, and individuals undertaking the work at the town’s burial grounds are described annually in a single line item. The most frequently listed chore was mowing grass for which a male, usually a neighbor, was paid between two and six dollars per year in this period. The farmer Isaac Day was paid for mowing and cutting brush at the West Burying Ground from around 1840 until 1850. His brother Amos Day, also a farmer, took over the job from 1854 until 1876. Periodically, these men were reported to have dug graves for paupers, for which the town paid them one to three dollars. Jonathan T. Colburn, relative by marriage to Amos Day, oversaw maintenance of the West Burying Ground from 1877 until 1905. While each burial ground had an individual to perform maintenance, the town had a single hearse driver for all burials. The hearse was kept at the East Burial Ground (now Fairview Cemetery).

Improvement projects occurred on several occasions in the West Burying Ground. The first to be recorded in the town reports appears in the 1858 volume which notes that the carpenter Ephraim A. Stevens, resident of Westford Center and later an architect responsible for designing the 1880 Parker Village Schoolhouse, was paid to build and hang a pair of entrance gates. Also contributing efforts to the project were the blacksmith Timothy P. Wright who supplied hooks, hinges and bolts for the gates and George Reed, the quarryman, who supplied granite posts. The posts with some parts of the hinges survive on the Concord Road side of the burial ground. In 1894 and 1895, a relatively large amount of labor was expended on the re-setting of gravestones. Reports appeared of leaning and broken markers which prompted efforts to tidy the burial grounds. While it is not specifically stated, it is possible that Colonial Period slate footstones, now quite rare in the cemetery, were removed as part of this work. The 1894 town report mentions that the “outer walls of a tomb in the West Cemetery have been relaid” but does not specify which of the three was repaired. The Patten-Prescott Tomb has a brick retaining wall with granite capstones and three slate tablets recessed in the wall. The unusual combination of materials suggest this as the subject of the repairs. In 1898, the stone wall along Concord Road, deemed unsightly and structurally untenable, was replaced with a fence (no longer extant) of turned chestnut posts and cylindrical iron rails. In 1899, shrubs and trees were set out as part of a landscape improvement plan.

The program of maintenance at the West Burying Ground did less to alter its appearance than did efforts to beautify Fairview (the former East Burial Ground on Main Street). A Committee on Burying Grounds which had been appointed in 1871 paid relatively little attention to the West Burying Ground and a great deal to Fairview. A survey and plan to improve Fairview in the style of a Garden Cemetery were drawn by the Westford civil engineer Edward Symmes. The chairman of the committee was the venerable lawyer and industrialist John William Pitt Abbot, resident of Westford Center, benefactor of the town, state senator, railroad president and future occupant of Fairview Cemetery. Under Mr. Abbot’s leadership, appropriations were made by the town for construction of stone walls, a gateway, landscape improvements, curving avenues and acquisition of additional acreage. This greatly enhanced the look of the old East Burying Ground and shifted focus away from the simpler West Burying Ground, which received a total of six burials between 1894 and 1897 while Westlawn received 103. There are indeed few late 19th and early 20th century markers in Westlawn.

Interments at the West Burying Ground between 1830 and 1900 include descendants of earlier industrialists and farmers previously interred here. For example, Jonas Prescott’s son Levi, (1771-1839) who, like his father, operated the forge on Stony Brook and lived at 25 Pine Street in Westford, is buried in the granite tomb marked “Levi Prescott’s Family Tomb 1839”.

Many generations of the Day family of farmers, with members living on Robinson, Graniteville, Flagg Road and others, occupy a large plot in the western end of the West Burying Ground. Burials include at least 19 family members and in-laws whose lives spanned the period 1797-1964.

Henry Herrick (1777-1869) and his wife Elizabeth (1789-1862) are buried beneath one of approximately six stout granite obelisks with capstones. Mr. Herrick was listed in the 1855 and 1865 census as a farmer although he probably had additional sources of income. He owned an ornate Federal style house in the village of Westford Center as well as other real estate a half mile from Westlawn on Robinson Road. Mr. Herrick was a civic-minded farmer, serving as overseer of the poor, tax collector, surveyor and road sign builder as well as town treasurer and selectman in 1843.

The Prescott family is interred under the marker with the appearance of a stepping stone or mounting block. The farmer Luther Prescott (1808-1904) was a representative to the Massachusetts General Court and station agent on the nearby Stony Brook Railroad. Mr. Prescott also ran the tavern in Forge Village that was the location of the mounting block until his death according to Gordon Seavey, a local newspaper columnist writing in August 1976. On the same plot are buried Mr. Prescott’s wife Sarah (1832-1904), their children Olive (1841-1903) and Sherman (1839-1901) and their families.

Civil War veterans are buried on individual family plots scattered throughout Westlawn. Approximately nine Union soldiers are identified by GAR crosses. Among them is Stephen Howard (1822-1863) who served with Co. M, 3rd Regiment of the Massachusetts Cavalry. Warren E. Hutchins died at Duvall’s Bluff Arkansas on November 29, 1864 while serving with the 7th Massachusetts Battery. The inscription reads “His country called. He answered with his life.” His brother Corporal Edward Everett Hutchins was killed at the Battle of Resaca, Georgia on May 15, 1864. He was a member of Co. F, 33rd Massachusetts Volunteers.

Information about communities with which Westford residents maintained trade relationships can be learned from gravestones. Stone carvers signed their names at around ground level on some markers, occasionally including the name of their town. By far the most frequent community noted on signed markers is Lowell, city of origin for stones carved by O. Goodale, T. Warren, Andrews & Wheeler and D. Nichols. N. A. Spencer of Ayer is the only carver not to hail from that community. Newspapers from the end of the period support the assertion that, when traveling out of town for commercial purposes, residents of Westford went either to Lowell or Ayer, typically on the Stony Brook Railroad.

The concept of Perpetual Care came into use in 1893. For a deposit of $50-100 to the perpetual care fund, Westford residents could provide themselves with a permanent program of plot maintenance. Also around this time, residents were requested to pay an amount of one to five dollars per year to pay for annual maintenance of their plots. Rising costs may have been due to increasing numbers of plot-defining features such as granite curbs and the several types of fence that must have been in use.

Interments slowed during the period from 1900-1950. Popularity of the larger, more refined Rural style Fairview Cemetery imbued the smaller West Burying Ground with the more primitive character of a Colonial Period burial ground. No curving avenues or bold stone walls were built. A pair of inexpensive iron gates had been added in 1902, but do not survive. Cemetery superintendent Albert P. Richardson called for suggestions to rename the West Burying Ground something “more euphonious” in 1895. His own suggestion was to name it for Colonel John Robinson but nothing was done at that time. Cemetery commissioners again requested suggestions for renaming the burial ground in 1903 and put forth the name Westlawn as a candidate. There was only one respondent who apparently concurred, thus changing the name. Lack of interest on the subject is in marked contrast to the campaign to rename the former East Burial Ground. New walls, gates and avenues inspired avid voting, ultimately in favor of the name Fairview. Without the Rural style improvements, Westlawn received a new name but little of the enthusiasm for reserving plots.

Approximately ½ the perimeter of Westlawn is surrounded by a chain link fence. Town reports record that it was installed in 1946 at a cost of $1117. Expenditures for maintenance nearly doubled after World War II, possibly due to mechanization of maintenance procedures. Cemetery business was carried out from at least 1937 though 1949 by the committee members Sebastian Watson, Fred Blodget and Axel Lundberg.

World War I and World War II veterans are buried in Westlawn, two of which have military markers. Stephen Kostechko served in World War II and is buried near the western end under a marble tablet with a low arched top. The legend “Massachusetts Cpl 332 Services SQ AAF World War II” and dates Nov. 6, 1914 - Dec. 31, 1955 appear below a cross. Nearby is his family in one of only a few plots in Westlawn occupied by residents of non-English descent. Carl F. Haussler (Dec. 8, 1892-Nov. 3, 1964) resides under a marble marker whose top is flush with the ground. He served with the Rhode Island Signal Corps in both World War I and II.

The local Colonel John Robinson Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution installed a granite memorial marker near the Concord Road gates. The 1968 bronze plaque commemorates the interment of Colonel John Robinson and “other revolutionary heroes” in Westlawn.

Colonial, Federal and Victorian period historical associations in Westlawn are largely intact despite interruptions by the small number of modern markers and by the chain link fence surrounding the yard. However, it continues to be possible, by observing the rows of arch-topped slate stones carved with cherubs, classical columns, urn and willow designs, and by recalling names so important to the development of the community, to get a strong sense of how Colonial Period residents of the Town of Westford viewed their burial places.

Westlawn Cemetery comprises all of the land within the triangular boundaries of the cemetery. It is bounded by Concord Road on the southwest and Country Road on the east. The cemetery encompasses 1.7 acres, described by the assessor’s office as parcel 34 on map 20.

Boundaries of the cemetery were determined by the Westford Historical Commission and by the consultant. Boundaries include all gravestones, burial-related buildings, structures, circulation paths and ornamental plantings. Chain link fence and stone walls mark edges of the cemetery.

SKETCH MAP NORTH

TOWARD TOP

While its name implies existence of picturesque characteristics of the Rural style cemetery design movement inspired by construction of Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge in the 1830s, the landscape layout, appearance and gravestone art of Hillside Cemetery adhere more closely to design characteristics from the Colonial Period. Acquired by the town from local farmers as a burial ground in 1753, it was originally called the North Burying (also Burial) Ground. Many of those interred here are significant in the history of the Town of Westford. War veterans, mill operatives, farmers and business people occupy the approximately 300 visible burials. Members of the Wright, Bates, Nutting, Keyes and other families influenced the town’s history and appearance and continue to do so by virtue of their artfully carved gravestones. The landscape is nearly flat with some grade changes to accommodate the slightly rolling topography. The burial ground is located at the northwest corner of Nutting and Depot Roads and remains in use. Markers, oriented in north-south rows, are made primarily from slate although other materials are present. Colonial and Federal Period grave markers appear in the form of shouldered-arched and flat-topped tablets. Granite and marble also exist.

Land comprising the old North Burying Ground belonged in the Colonial Period to Ebenezer and Thomas Wright, local residents who were probably farmers. The appearance at the time was likely that of a field of grass with a few small slate gravestones, a description still largely applicable.

Boundaries of the cemetery are lined on the south edge with a granite slab retaining wall capped with spilt coping stones and on the east by a granite fieldstone wall, also with split capstones. West and north boundaries are low dry-laid fieldstone walls. Entrance to the cemetery is thorough openings in the stone wall along the Depot Road (east) side and in the southern stone wall along Nutting Road. The Depot Road entrance is articulated by round piers built of cobblestone about five feet in height. Additional entry is via stone steps in a gap in the wall at the southern side. A modern flagpole occupies a site just inside the east entry.

Plot definition occurs in approximately four instances with simple granite curbs that are located either flush with the ground or as much as 18 inches in height. The Smith family plot has granite curbing approximately a foot in height with granite steps to access the slightly elevated plot. Single steps on the east and west are flanked by low octahedral piers. The step is inscribed “T. Smith” in memory of Thomas Smith (d. 1829 at 91 years of age). The William Chandler Family plot has slightly taller curbs with tooled edges. Curbs enclose square and rectangular parcels of from eight to twenty feet per side. A single asphalt path traverses the cemetery from east to west near its northern edge.

Hillside Cemetery reflects trends in gravestone development in its variety of slate, marble and granite markers. Slate is the oldest surviving material used for marking burials and is carved in shouldered-arched and flat-topped stelae (rectangular slabs or tablets). Ranging in height from one foot to five feet, this type of marker can demonstrate a relatively crude, hand cut appearance, a well-designed and possibly machine cut sharpness and several levels of workmanship in between. Quality of workmanship of the slate marker is sometimes obscured by the fact that the stone has deteriorated or been broken. Inscriptions also vary in quality and detail. The simplest have fine, narrow letters with little relief or depth. Later slate stones from the 19th century are more likely to demonstrate clear, deep, stylized letters with a pronounced serif and well thought out organization relative to the shape of the stone.