It was a dark night, a memorable night. Don Elman and I had taken an hour to get a cab, and gotten soaked in the bargain. We finally shared one with 6 other people, and wound up in Ghirardelli Square.

We had come down to San Francisco on January 16th to attend the Apple World Conference as press representatives. The day had started early with the much-leaked introduction of the Mac Plus, and had whiled along with speeches from John Sculley, Alan Kay, and others. For the most part, it had all the excitement of a political convention where everyone knows the outcome.

But still, it was interesting to hear the Apple's gurus talk about what turns them on. Kay had talked about The Inner Game of Tennis, Dynabook and Vivarium. Sculley had tried to express his overall visions about where Apple was going, and was solicitous towards Steve Jobs; indeed their lawsuits against each other were settled the next week.

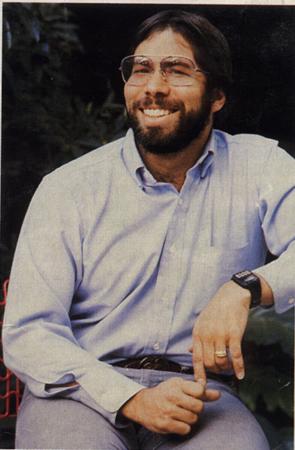

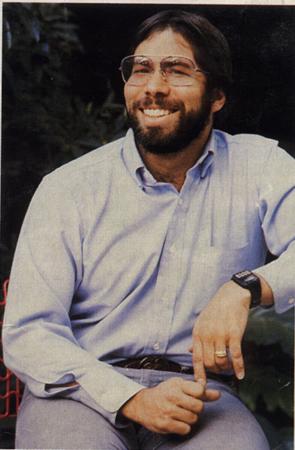

But as Don and I were entering the restaurant, I knew this was going to be the best: The Woz, talking to his favorite audience, User Groups.

And what a collection: It seemed as if every group in the country, and probably some foreign countries, had sent one representative to San Francisco. Large groups, like ours and small, 30-member groups like Eugene's Mac SIG, were all represented in a friendly assembly.

It had a Woodstock ambience; we were here to drink, dine and take in the words of one of the most creative, progressive engineers this country has produced, Steve Wozniak.

Contents

Woz's Early Interests Woz's Early Interests

TV Jammer

The Dial-A-Joke Days

Programming Class

Designing A Computer

Homebrew Computer Club

Computer Kits

Growth Of Homebrew

Woz's Early Interests

I'm going to cover a topic I've never talked about before - how Apple got started. My own perspective ... it's an easy story. I was pretty much self-taught in computers. Fortunately, my electronics teacher knew enough to get me out of school, because I would play pranks out of boredom. Even though our school didn't have computers, I was able to encounter them a little bit. I went off to my first year of college, and, you know, you grow up with electronics when you grow up in Silicon Valley, and your parents are engineers. Other kids' parents are engineers and they run their house-to-house intercoms through other people's lawns - not knowing anything about trespassing rules.

TV Jammer

Well, after class, we always looked around for fun things to do - electronics. It's one of those things you can do a little bit of magic with. People don't know where it comes from. And so I built this little thing called a TV jammer. Any of you know what a TV jammer is? Well, it's a little, tiny one-transistor circuit; you know, you dial this little capacitor around and it jams a TV channel. It just jams it. Well, I took it down, and I wanted to try it out on some of the students at the University of Colorado. And I went to another dorm. I didn't go to my dorm because they knew me too well. But, I went to another dorm, and went down to the basement, and 20 kids are watching TV, and I sit in the back where it's nice and dark, and I hold this thing in my hand with a battery in it. Two minutes and the picture gets fuzzed up, you know. A friend of mine runs up to the TV - he's seen all the pranks - he hits it. "Bam!" it works. A few minutes later, it goes bad again. He hits it. Every few minutes he's got to hit it harder and harder, you know. And it works eventually. It's an inanimate object gone bad. Well, it's really shocking because I've discovered that if you really experience it, it only takes about a half an hour. Any college kids, anywhere in the country - it doesn't matter how peaceful they are. This is, you know, Vietnam days. It doesn't matter how anti-violence they are. They will be throwing chairs on top of that TV set. A TV set does not count like a person. They would be pounding that thing. For weeks they had a guy stationed, and if the set went bad it was his job to hit it and make it go good. And every once in awhile he would have to hit it pretty hard. Sometimes it wouldn't go good and they would get up there and start fiddling with the knobs, and it would go perfect. They would pull their hand away - bad again.

One of the things they learned is where your body is. I should have taken a course in psychology, you know; but I was just learning, I was just learning what you can put people through, more or less.

One time they messed up the TV real bad and the repairman came, and he said it was the antenna, the antenna was mixing channels. And that made sense - you know, a radio. So the next time it went bad someone commented, "It's the antenna." They held it up in the air - it went perfect ... for a few minutes. Another guy stands up higher and it's good. For awhile. And then he stands up on a chair to make it good. And it goes bad again. He stands on his toes on the chair and the TV works. He comes down on his heels and it doesn't work. I don't know, it should have been rats in a cage. It was a great opportunity.

Another time, man, there was a whole bunch of people up there trying to fix this TV set, and all of a sudden I notice that this guy has his hand on the middle of the screen and he has his foot up in the air on a chair. So I let the TV go good - I let the TV go good. He moved his hand away and I made it go bad. They discovered the use of their body positions made it work. They discovered that if his hand was on the set and his foot was in the air then it worked. He said that it was a grounding effect. So for the next half an hour they watched the last part of Mission Impossible with a hand in the middle of the screen.

Now we're getting more serious. Down to the first computer class I was going to take in school, the initial course. They didn't teach to undergraduates in those days, so it was a graduate course, but it was just an introduction to the program. The odd thing is that they had a new building, a new engineering building. The class was rather large, so one third of the class got to see the professor live every day, and two-thirds of us got to see it on four TV monitors in another room. They didn't use perfect cable TV. It was on channel three. Well, I built my TV jammer into a magic marker, well hidden for goodness sake. I came into class, and I tune it in, and sure enough, it jams all four sets. Some are worse than others. Then three TAs - this class is much smaller than even this group right here - but three TAs stand up, and they're looking at us, they're looking us over, you know. And I'm scared. I freeze. I know what they're looking for. I'm not going to reach over to my magic marker and flip a switch off, you know. I got really scared. How am I going to get this thing off? It's been over 10 minutes, 15 minutes. I'm thinking at the end of class I'll just walk out, and they won't know who it is. About ten minutes before class is over there's a guy right under the set that is jammed the worst. He decides to leave early. He gathers his books together and gets up to walk out. I couldn't resist. I grabbed the magic marker and made the TV kind of flutter, in and out, in and out, as he's walking. He walks out the door; the TV's perfect. And I see a TA point. He says, "There he goes." So you learn something, you know ... always frame someone else.

The Dial-A-Joke Days

It's kind of neat to hear some of the stories that Dial-A-Joke brought up. It was the first Dial-A-Joke in the San Francisco Bay area ever. Steve Jobs and I had been serious phone freaks selling incredible blue boxes. I paid for calls to my family, friends, to my relatives, to this and that - all the calls I would have normally made. But I got on and started calling Japan and London, and I learned how to conference a line across the satellite and go back and forth across the world - only for the sake of exploring the system. That phantom world of the Cheshire cat - where does it end. And you try to find bugs that will maybe help the phone company. I discovered joke machines in other cities!

Somehow, some of us are just that way - you just have to go out and do it, because it's a good idea. It doesn't matter if it's not the standard, or some rule or procedure in your life. So I ran Dial-A-Joke, you know. It was a lot of fun.

(To member of audience): What school did you go to?

"Presentation."

Presentation High. I can't remember if that was a new one, but I remember that was on my list, because what I would do is that I would take live calls - I got so good at this that I would take live calls. And they wouldn't believe I was live. But I would always ask them - Is there some quirky teacher or some weird thing you could tell me - a funny story about your school? And I had this huge list, and I remember asking someone, "What school are you from?" and they would tell me a school and I would say, "Oh, does Mr. Sarnson still wear those funny red pants?" Then you would hear this "Yeah". Then I would try to insult them. These were kids and they would try to insult you back, you know. But I cheated and kept the "book of 2001 insults" open.

Well, oddly enough, one time, I went through a lot of phone numbers, because anyone that had a slightly different number - my machine was in Cupertino - you couldn't use your own machine in those days. I had the phone company's machine. It rang - "BBBBLLLBBB" - loud - 2000 times a day in my apartment - called the something 700 - it was a very heavy, heavy duty machine. And the phone company had to replace it once a month. It wore out. Anyone who had a phone number a little different from that would get hundreds of calls a day. At the first time some lady called me up and she was so upset, because her husband worked nights or something and they couldn't take all these phone calls. Well, I kept switching the number around, and I finally got a nice easy one to dial. I called up the phone company and asked, "Can I have 255-5555?" They said they couldn't do that. I said, "Can I have 255-6666?" And they checked and they said, "Okay, you can have it." And I figured that would solve my problem. Then one day these people came over from the local, the largest ski shop in Northern California - it's called Any Mountain. Their number was one digit different. They said that they were afraid to answer their own phone any more.

The Polish-American Congress Incorporated, one of the major cultural groups for Polish people in this country - they found out who I was and their lawyer sent me letters threatening me with law suits if I kept telling Polish jokes.

I thought, "Well, what do you mean?", you know. So I called them up and told them, "I'm just doing this just for fun, for humor, you know. Laughter is worth more." But oh no - they weren't going to listen to me. They sent me another letter.

Well, I talked to a bunch of my callers - "What do you think of this? They're going to sue Dial-A-Joke. Why don't you call them up and tell them what they are full of."

The next letter from their lawyer accuses me of making obscene, malicious phone calls. I thought these kids would be smart enough to just call them up and say, "Hey, let him tell Polish jokes." Well, finally, it turned out that they didn't have any principles, their only word was that Polish jokes were bad. Well, I said, "What if I told Italian jokes." They said, "Fine". So I switched to Italian jokes. And oddly enough, it really struck me, a month later they actually sued a TV personality, Steve Allen. And it went all the way to the Supreme Court, and it finally lost, so I went back to Polish jokes. That was about 1974. Well, in 1984 I received their highest award of the year from the same group, called the "Heritage Award", and they don't know it's the same person.

Dial-A-Joke-it was great. One time I did this April Fools joke. I would say, "And for a real good joke, dial 968-1999." It's a number that always answers and keeps ringing. It's a recording of a ring. Or it's a busy signal. And I would talk to the people a week later and they would say, "Well, I've been calling that thing for a week." And I would say, "Well, you've got to try real hard."

Another time the machine broke down. I called the phone company and asked them to come fix my machine. I said, "Send the guy after five, because that is when I get home from work. I work at Hewlett-Packard in calculator design."

Well, I came home at five and there's a note on the door from the guy and he says he was there at two.

So I called the phone company up again. "Make sure he gets there after five because that is when I get home. I want to be there while he's working on my phone." So I get home and there's a note on the door - "I was here at four." And I called up the phone company and I was very, very upset, and I'm yelling, "Make sure he's there after five the next time." I go home and there's a note on the door - "I was there at three."

Okay, okay, peace mode. I'm not upset. I just hooked up my only answering machine that worked. I called the phone company and said, "My answering machine is broken. Please send the guy out after five, tomorrow. Thanks." I put my only message on - I said, "Hey, for any of you who want Dial-A-Joke, the machine broke down and the phone company hasn't fixed it. If you want Dial-A-Joke back, dial 611... and have your friends call too."

So the next day, I was busy all day with meetings at work. I came home, just a little before five, and took my illegal machine off the wall. I called 611... just to see - sample things. I said, "I have a complaint." They said, "I know, Dial-A-Joke." I said, "How did you know?" They said, "Every other call today has been for Dial-A-Joke." Five o'clock on the nose the repairman shows up - with his supervisor. I let the repairman fix the phone, and I let the supervisor stand out in the rain, and I gave him a little book to read called, "I'm Sorry, The Monopoly You Dialed Is Not In Service."

(Audience): "Is it still in print?"

Probably. It might be. It was a real book. It really was.

(Audience): "You had a good user group."

Yes. I don't make these jokes up. These are not jokes.

Now, I'm going to take a little diversion. So I'm going to make a joke. This is the time that Alan Kay died and went to heaven. And, boy, they were looking over this list of how he did down on earth, you know. And they said, "Well, it's not too good of a record, but, well, we'll let you in. But for a couple of weeks you've got to take the claim for this really, really awful looking woman. You know, you've got to help her out. You've got to get her anything she needs. You've got to be, you know, you've got to atone for your sins." He said, "Sure, I'll atone, you know. I'll do it." And he's walking around and he sees John Sculley walking by - with Bo Derek. He's walking Bo Derek around! He thinks, "Hey, this isn't fair." He runs back to God, and he says, "I thought that in heaven everything was supposed to be fair." God says, "Heaven is fair ... Bo has to atone, too."

Programming Class

I was in that programming class for fun. And you don't realize that there is a real financial world. Things are accounted for. Things have costs. You don't realize that. You're in the class so that you'll gain a computer number and you can use their computer time, right? You don't realize that the class had a budget, and such. I started running every single program, every single table I could find in mathematical handbooks. I started writing programs to run off fifty pages of them, and punch up new cards to continue where it ended. I ran it through three times a day, six programs running - about eighteen programs - accumulated stacks and stacks of paper, you know, from all of these programs. And the professor ... boy, he called me in at the end of things, because I used my own number. I should have used someone elses, but I thought I was a student. He called me in, and said, "What are you doing?" I said, "It's FORTRAN, it's a FORTRAN class." He said, "This is not what we teach here." He said, "Are you trying to get me or something?" He was going to make me pay four hundred and twenty dollars if I went back. So I didn't go back to that school. But the school put me on probation for computer abuse. This was in 1969. Computer abuse!

And, basically, it got home the point. I just wanted to run a bunch of fun programs and all, but it was their computer. It wasn't my computer. It was their computer.

Designing A Computer

Okay. Around that time, a lot of mini-computers came out. This was the mini-computer flurry. It was like micro-computers were to come out maybe half a decade later. One of them was the Data General Nova, and that computer was strange. In those days, they would introduce a brochure for a new company with a new product in mind, and oddly enough, on the last page of the brochure with pictures of all their key executives, they would even rate, equally important, the instruction set of the mini-computer.

For some reason I stared at this thing. Ever since high school I had been designing every mini-computer that came out. I would design my own versions. Over and over. Just to get better and better at designing them on paper. I looked at this instruction set and I was a little shocked. They claimed to have one instruction for almost everything. They took two of the bits as a register, and two of the bits meant an operation, one bit meant whether you shifted or not. I looked and thought, "Boy, it's amazing. You can do every, single, useful instruction, and yet they broke it down into little parts. Every little bit had meaning."

I sat and designed it, and right away I realized that there wound up being about half as many chips to design that computer as any other one. It had just as good an instruction set, but it took half as many chips to design. For the rest of my life, my philosophy was going to be trying to look for that little improvement, the simplification that can do as much as if simplification weren't there. There's tricks like these, efficiencies. And it became very important to always look for a way to do a circuit with total functionality, and yet fewer parts.

Homebrew Computer Club

I'm going to skip ahead a few years. Let's say 1975. You know, this is when micro-computers are about to hit. Popular Electronics puts the IMSAI computer on the cover [actually, the Altair]. The Homebrew Computer Club was the first computer club in the country to start. This was started in the Silicon Valley area. It moved around from city to city for the first year. Basically, I got tricked into it. I had gotten out of computers for a few years. I was running Dial-A-Joke. I was designing calculators at Hewlett-Packard. And the Homebrew Computer Club started.

I wouldn't have gone if I had known that is what its name was. But my friend came up and tricked me. He said it was for people who have terminals and things. Okay, well, I had just designed my own terminal, because my life was electronics. I worked designing calculator chips for Hewlett-Packard, but electronics was my life. It was my hobby. I saw a Pong game in a bowling alley, and I designed my own Pong game. Steve Jobs and I got a contract to design Breakout for Atari. I designed that game, the arcade Breakout. I do these things. I went over to Captain Crunch's house. Captain Crunch was one of the early phone freaks who discovered that a Captain Crunch whistle would make calls for you, for his friends overseas. I was at his house and in his basement, he had a terminal and he's logged onto all these computers on the ARPANET, and he's playing chess games and the like. And I'm thinking, "Wow, I want to do this." So I designed a video terminal.

Well, this friend tricked me into coming to this club for terminals. And everyone starts talking numbers that I had never heard before. "8080, 8008, Intel ..." And they start talking phonetics of computer instructions. And I'm feeling very, very shy. It's like, I'm way out of it. These people are all into what is going on in this micro-processor world. And I never heard any of this stuff. You know, I'd just been working as an engineer for three years. I did walk away with a renewed interest in computers. It gave me motivation. Somehow I was going to get back into this.

I looked over the instruction sets on micro-processors, and I said, "This is mini-computers. This is what I taught myself back in high school." The first club meeting was in a garage of a guy named Gordon French. They're sitting around trying to debate should they really focus on the new 8080 microprocessor, the first big, low-cost, computer micro-processor, or the 8008 which came before it. There was a lot of sentiment, and the people speaking, "the 8008's a good machine and it's still around, and we can do a floating point add in 2.5 seconds with it." And it still has promise.

The first computer magazines were starting around the same time. I had a friend from the lab at HP that got me into the computer magazines. Byte magazine was the first big one to start. Wayne Green, one of the ham radio magazine editors, came out with Byte magazine, but his attorney told him for tax reasons, to put it in his wife's name. But then they got divorced, so he lost the Byte magazine. He had to start KiloBaud about a year later. When they first heard of KiloBaud, he called it "Kill-a-Byte."

Computer Kits

Okay, the typical computer started coming out. The first talk was that somehow there were a whole bunch of these little hobby computers selling. They were all kits. That meant that you had to pull out a soldering iron, pull out a bunch of chips and a PC board, and solder them together. You had to bolt the PC board holders into a big case and bolt the transformers on. This is the normal thing that ham radio operators go through when they build equipment. And so, basically, the first computers were only for this hobbyist market. People who read Popular Electronics and read the Ham radio magazines like 83.

It turns out that they were all kits. They were all in the paradigm of a mini-computer, a big square box with a bunch of binary lights on the front to tell you what was going on in memory, and a bunch of binary switches. You could set the address, one memory address on one set of switches, you could set the data on another set and you could push a button and it would store that byte into the memory. That was the only way you could look the memory up in this early a date.

The first interfaces that came out that would let you load data in a little faster were designed for teletypes, because it was the only type of machine around, the only printer that was around in surplus - a surplus market left over from mini-computers. It cost a thousand dollars when the computers cost four hundred. And then you would still have to spend ten minutes toggling in, byte-by-byte toggling in a short, little program that will read another program off of the paper tape that comes on the teletype.

That was the hobbyist viewpoint of what these "home" computers were. The word used was home computers. We started talking that home computers were going to flood America. It was going to be a revolution. Companies like HP and IBM, you know, and every major company just ignored it. No, these are just a bunch of kids driving around in a mobile home, trying to sell a couple of computers out of it, and it's never going to go anywhere.

I decided, of course, that I was going to own my own computer, somehow. I couldn't afford to buy even a four hundred dollar computer, though. You know, my apartment in Cupertino made me pay cash, because my checks didn't always go.

Growth Of Homebrew

Okay, this club is going right along It started out with forty members the first night, even though it's raining outside. It's a dark night, but it's a very memorable night. People in the club stand up and announce who they are. Out of those forty people probably about five or six of the first major micro-computer companies were started. Somehow, we all had the same feeling that we were on to something happening. The club developed a newsletter, and typically there would be a short, little program - how to generate a random number. You know, it was always advice. The whole motive of the club was: Give to help the others. People would stand up and tell about everything that was going on in microcomputers. People would stand up and tell everything that was going on in their company. People would stand up and tell all the rumors of the business that were in Computer World magazine. This is back before InfoWorld existed. And people would stand up and say that they had such-and-such piece of equipment if anyone wants it or needs it. Other people would ask for help.

And Lee Felsenstein, who was the organizer of the Homebrew Computer Club, set it up in such a way that we were, basically, an anarchy. At every meeting he would announce, "The Homebrew Computer Club does not exist." And everyone applauded. It turns out later that they did have to exist, because they had to be a corporation to be non-profit. So it had five members in the end - the board of directors. Jim Warren, from a couple of the local magazines and a couple of the local companies, would always spend about half of the meeting telling us every rumor, what every company was doing, and where things were going.

Randy Wigginton, who has written MacWrite in recent years - quite a story there, but I don't have time for it with this whole story - was at the club, and he was just a high school kid. He had gone to the same high school that Steve and I went to. Steve didn't attend the Homebrew Computer Club; I did. And that is how I met Randy. I met him because he was in charge of a local time-shared computer called Call Computer. We had an account for our club; we could all call in at the same time and talk to each other on our terminals or on teletypes, and Randy was running this thing.

Well, I just simply did a little scanning, and figured out that I could load up my computer so it would grab the file as soon as it was available, and run a program that instantly would dump a ton of Polish jokes on everyone's terminal for the next half hour. And they could never figure out where that was coming from. Every meeting, Randy would have to get up and sort of apologize for why it wasn't working.

Marty Spergel was one of the local surplus store dealers. He would buy parts from Hong Kong and sell them in surplus stores and all this. He was later to be the guy who did the M&R Sup'R'Mod modulator for the Apple computer. The story behind that is really more that it was designed in Apple, but we didn't want to sell it. So Marty sold it; and he made a lot of money off of it. He would come to the club and try to offer us his 2102 IK static RAMs for $2.10. A real good price. Someone else would raise his hand and sell them for $1.86.

One of the guys, I'll just call him Dan, came one time and he had gotten one of the first copies of Microsoft BASIC. BASIC was one of the first languages to come out for microcomputers around this time. And it was written for the 8080 microprocessor, and was delivered on paper tape. The accepted input-output device was not yet going to be video, not yet cassette tapes, and who knew if floppies would ever be there. The only way people would ever get it in was if they had a teletype they could load this paper tape in for half an hour, and load BASIC into their machine.

Well, we got one for the club, someone brought one in, and Dan borrowed it and two weeks later, he came in and he had 20 copies of it off of a high speed punch. So he contributed that to the library, and he made a rule. The rule was that anyone who wanted to could borrow it, but you had to bring back more than you took. It solicited the first letter in the industry of "Stop This" from a publisher. And everyone thought that it was ridiculous that BASIC should cost more than your computer.

The people that attended were pretty much like those in user groups that I see around the country. I've been going to so many for so long, and typically they weren't really the manager types. They were just sort of the technicians and what not; very few of them wore suits. Not even as many as in this group. They were just sort of the fringe element, the people who weren't really accepted in their place of work. But I noticed one thing; they were all from some sort of place that had a computer. And boy, they wanted access to it. They had all taken computer courses, but they didn't quite have access to it very much at their company. It was very restricted or indirect. And they all had a good, strong feeling that they've got to have their own computer.

I was there watching this really intriguing thing; everyone was talking like it was a revolution-just to hear all these rumors. I was there more to watch all this interest, than to have my own computer.

Everyone there was a typical technician type, the person who comes solidly into maybe math & electronics calculations and everything calculates out to this one pure answer: zero or one, pretty much. That sort of mentality was common in the club; very pure people, you could always trust them that they'd talk a little strangely, but only in terms of that there is a logical calculation for everything that could ever happen in the world. And, you know, I was one of those types at that time; I will never be as pure as I was then. I will never be as pure and know that I would always have happiness because I was calculating.

A very non-political group - anti, anti politics. Like I said, we described ourselves as an anarchy that did not even exist. That's pretty much a feeling that's common among user group-type people: stay out of politics. I have had many politicians try to approach me, or have become associated with them, and so many times I have to dodge or deliberately avoid them. Even tonight, I'm avoiding some things going on.

|